Honour Roll and Historical Society

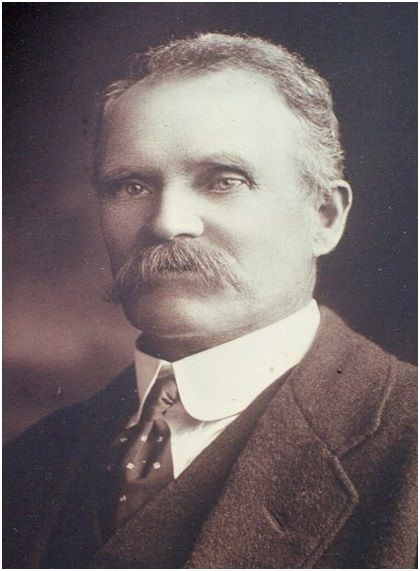

HOWIE, Mr Charles Pringle (Charlie)

1859 - 1951

Charles Pringle Howie was born in Geelong, Victoria on 10 December, 1859. He was the second of three children of devout Scottish Presbyterian immigrants who had met and married in Geelong. His father died when he was only two years old, and thereafter his widowed mother struggled to raise the children, relying largely on the charity of her parents, siblings and the congregation of the United Presbyterian Church, which she and her family all attended.

After rudimentary schooling, at about the age of thirteen, Charles (more familiarly known as Charlie) was apprenticed to a pharmacist; however because the pharmacist ill-treated him, after a few months his mother had him apprenticed to a plumber instead. His meager apprentice’s wages provided her with her first regular income since her husband’s death. Plumbing was then the trade Charlie followed for some fifty-five years, until 1934 when he was seventy-five.

After spending his youth in Geelong where he played football with the Geelong Football Club, Charlie decided to try his luck on the central Victorian goldfields where the expanding mines and mining towns promised to generate more work for plumbers.

He arrived in Creswick in 1882 at the age of 22. At first he worked for another plumber but in 1884 he set up business in a shopfront with attached residence at 64 Albert Street, taking over the premises from its previous owner, a fishmonger. The building is the still-to-be-opened Red Heap Cafe. He developed the land behind his shopfront into large, beautiful and productive flower and vegetable gardens with an orchard at the rear and a worm farm to provide the bait for his fishing expeditions.

In the year Charlie Howie settled in Creswick, he took part in the rescue effort during the Australasian Mine disaster in North Creswick in December, 1882. As a plumber he had the task of maintaining and operating the pumps hastily installed to pump out the flooded mine.

About this time Charlie also made the life-changing decision to quit the congregation of the Creswick Presbyterian Church and attend the Wesleyan Church in Victoria Street instead. He felt he had been “cold-shouldered” by the Presbyterians and that they considered themselves superior to everyone else. Comprising mostly the families of members of the professions, they looked down on blue-collar workers like Charlie Howie, the young plumber from Geelong.

At the Victoria Street Wesleyan Church he soon met the demure teenage Annie Harris. She was one of a family of six, and her father had recently run off to Melbourne, leaving his family. Annie and Charlie married in 1884 when she was only seventeen and raised a family of nine children, six of whom survived into adulthood. All were educated at the Creswick State School and did well in life as a result of their upbringing.

Annie and Charlie’s involvement in the Victoria Street Church continued for the rest of their lives, fifty-one years in her case and fifty-seven in his. He taught Sunday School for fifty-four years, sang in and conducted the choir and served on the church councils and committees. He also undertook the maintenance and repairs at the church, usually at his own expense. The Howie’s raised their children to be committed Methodists.

Charlie was also a civic-minded fellow with active membership in various community organisations. These included a term on the town council; membership of the Creswick Hospital board, on which he served two terms as Chairman in 1902 and 1935. He was also a member of the local fire brigade volunteers, of which he was Captain and for which he received a long service award.

He had as well, many years membership and a term in 1905 as Master of the Havilah Masonic lodge. He had a term as President of the Creswick branch of the Australian Natives Association, the pre-Federation lobby group and medical benefits society.

During World War 1, in which three of his sons served overseas with the AIF, he became President of the local Creswick branch of the Soldier’s Fathers Association, a patriotic rganization formed to rally support for armed service personnel sent to overseas theatres of war. His wife Annie became the local President of the corresponding women’s rganization, the Soldiers Mothers and Wives Association.

After the war, Charles was Secretary to the committee which had the war memorial constructed. Through such voluntary effort he did much to foster community development in the Creswick district.

As a master plumber and gasfitter, Charles Howie trained many apprentices in the fifty-two years he practiced his trade. He was also responsible for installing important parts of the town’s and district’s infrastructure. After the Creswick gasworks was constructed he won the contract for laying the pipes to, and connecting subscribers’ homes to the supply. He also won contracts for laying the water pipelines from local reservoirs such as Russell’s Dam to the town, and for reticulating the supply to households. He also installed the water pipes and air ducts for some of the deep lead mines. He also made and supplied water tanks and installed and maintained many of the windmills on the farms of the district.

Charlie Howie was a short, nuggetty man, only five feet five inches (1.65M) tall but within his family circle he was a strict pater familias of the Victorian era in which he grew up. A man of strong convictions, he had firm views in most matters, but he was also kindly and generous, had a wide circle of friends and was greatly respected within the wider Creswick community.

Business & Tourism Creswick Inc.

PO Box 214

Creswick, Victoria, 3363

info@creswick.net